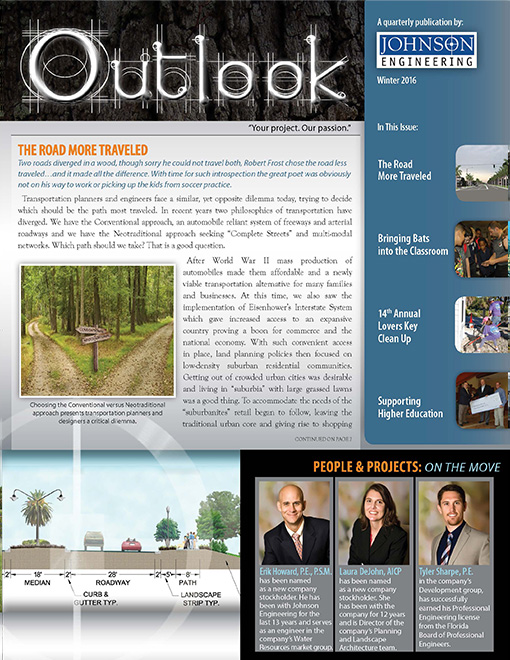

Transportation planners and engineers face a similar, yet opposite dilemma today, trying to decide which should be the path most traveled. In recent years two philosophies of transportation have diverged. We have the Conventional approach, an automobile reliant system of freeways and arterial roadways and we have the Neotraditional approach seeking “Complete Streets” and multi-modal networks. Which path should we take? That is a good question.

Transportation planners and engineers face a similar, yet opposite dilemma today, trying to decide which should be the path most traveled. In recent years two philosophies of transportation have diverged. We have the Conventional approach, an automobile reliant system of freeways and arterial roadways and we have the Neotraditional approach seeking “Complete Streets” and multi-modal networks. Which path should we take? That is a good question.

After World War II mass production of automobiles made them affordable and a newly viable transportation alternative for many families and businesses. At this time, we also saw the implementation of Eisenhower’s Interstate System which gave increased access to an expansive country proving a boon for commerce and the national economy. With such convenient access in place, land planning policies then focused on low-density suburban residential communities. Getting out of crowded urban cities was desirable and living in “suburbia” with large grassed lawns was a good thing. To accommodate the needs of the “suburbanites” retail began to follow, leaving the traditional urban core and giving rise to shopping malls and strip malls. Demand continued and increased automobile traffic required more freeways and arterial roadways to support the growth. New gated communities gave homeowners a sense of security but fewer access points made transportation reliant upon arterial roads generating congestion at their intersections.

Such conventional prosperity and growth gave way to “urban sprawl”, communities so spread out that effective transportation became impractical, delay and congestion became inevitable. Florida is especially affected in this regard. Many transplants from the North and Midwest came down to escape larger cities and cold winters. Living with a little grass between you and your neighbor, warm and secure behind a fence certainly has its appeal. We got what we wanted and have now realized maintaining such infrastructure is not easy or cheap, and continuing the practice indefinitely is unsustainable. So what do we do about it? We tried concurrency, the idea that development could not take place until adjoining roadways were brought to an acceptable level of service, i.e. pre-determined level of congestion, concurrent with the development. Concurrency was great in theory but not so much in practice as the solution was typically “build more lanes,” and the most qualified locations to develop according to the concurrency formula were the locations that were not congested, contributing to more sprawling low density development patterns. In some cases, more lanes may be the answer, but where does it stop? When have we reached a realistic and sustainable capacity?

In steps the Neotraditional approach. Synonymous with several other catchy monikers, such as New Urbanism, Sustainable Development, Smart Growth, etc., the approach shares the belief that a return to planning patterns and transportation modes that existed in traditional urban cities prior to World War II is our best bet. This school of thought advocates a holistic approach to mobility and “Complete Streets” that provide ample opportunity for alternate modes of transportation such as pedestrian, bicycle and transit so that we are not forced to rely on automobiles and developments are not forced to consume land with large parking lots. To reduce the reliance on arterial roadways Neotraditional planning promotes compact community development with increased density and integrated roadway networks with numerous smaller roads interconnected in grid fashion to allow more options in getting from point A to point B.

So which approach is correct? Should we continue to follow conventional methods and add more lanes to our existing roads or should we go back to what worked before automobiles were everywhere? The answer is both and neither. A key tenant in planning is “context sensitivity”, the idea that there is no one perfect answer and that the right thing to do all depends on where you are. This is critical in transportation. There is no blanket solution, the right thing to do depends on that unique set of circumstances and what is going to align with achieving the community’s overall vision for the future.

Cities and existing developed areas still need to be connected. If conveyance capacity is a problem, more lanes may very well be the solution. If you have congestion in an existing built-out area rather than blindly adding lanes, perhaps you should consider some strategic interconnections of existing roadways with some bicycle and pedestrian facility upgrades to provide a better network. If you have an existing multilane road in a declining neighborhood, perhaps instead of retaining that conveyance capacity a lane reduction with the addition of sidewalks and landscaping may better serve the community. The answer will not be the same for every situation.

Where planners and engineers go wrong is when they attempt to force a singular solution regardless of the context. We must remain open to multiple potential solutions. In reality, as communities grow, we come to many forks in the road. Choosing left or right, more traveled or less traveled, Conventional or Neotraditional, is not an easy decision, because it changes based on your circumstances and the community’s goals at the time. The prudent traveler, engineer and planner must evaluate each situation on its own merits before deciding which road to travel. From there we can affect the difference we are looking for.

For more information, contact Ryan Bell, P.E., PTOE at [email protected].

Prologue

While most people read it as a serious reflection of life’s decisions, Robert Frost wrote the “The Road Not Taken”, where this famous quote came from, as a joke. One of his best friends was a writer from England, Edward Thomas, and on walks through the woods, Thomas was very indecisive and would fret over decisions of which fork in the road to take, for fear he was going to take the wrong one. It was intended in good fun but the chronically depressed and unstable Thomas took it as his best friend mocking him and criticizing his indecisive nature which he considered a personal weakness. After reading this he decided to do something about it, rather than sticking with writing, which he was good at, he took the road less traveled and voluntarily joined the army during WWI. Later thrust into active duty, Thomas was sent to France and killed within two months of arriving. The road less traveled may in fact make all the difference, but it could be a very, very bad difference.